I have been trying to write about the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11 since last week. I wanted to write a piece that talked about where I was on that historic evening during the summer of 1969. The summer was tumultuous for all sorts of reasons - political, historical and personal. It was one of those touchstone moments in my life where everything was changing and falling apart around me, and I wouldn’t understand the significance of the confluence of events until much much later. This is one of the reasons I was having such a hard time writing about it from my adult perspective – I couldn’t find the narrative voice of a younger self who could tell the story with immediacy and honestly.

Last night in writers’ group, for our writing prompt, Alison Hicks placed dozens of visual images on the floor and asked us to find one that called to us. I found a surrealistic landscape with a haunting moon hanging low in the sky. I wrote July 20 1969 on the top of a clean page, then made a decision that helped me get inside of the narrator’s mind.

I created a third person limited narrator that was telling the story from the perspective of a 17 year old girl. Here’s what I wrote:

July 20, 1969

It is early evening and she doesn’t remember how she got here or which one of her girlfriends gave her a ride in their father’s Chevvy. She knows one of them did, Randy or Andie, maybe because she doesn’t drive. She’s been here for hours, and the tweed fabric of the orange sofa chafes against the skin behind her knees as she leans forward, still staring at the large black and white TV – an RCA floor model in a maple cabinet, console type with shiny metallic woven cloth covering the speakers on either side of the flickering screen.

She’s not alone, but she sure feels like she is. She hasn’t spoken to anyone since Randy, or was it Andie, left after seeing what was going on here. There is nothing more boring than a bunch of scagged out boys in front of a television set in the unairconditioned living room of a semi-detached brick box in Northeast Philadelphia. She felt the same way, about the boredom that is, but what kept her here was Dock – the boy whose house it was, the boy whose parents left him alone for two weeks while they drank mai tais and attended luaus in Honolulu, and the boy she had been madly in love with since she was fourteen.

It was the summer of 69, the summer before 12th grade, and less than a month before Woodstock and her planned getaway with Dock, though she hadn’t quite figured out what to tell her mother, or even how she was going to convince Dock to take her along with him and the boys when they went to the rock festival.

She let her eyes stray from the television set and wander around the room. The shades were drawn and the volume on the TV had been turned off and the stereo turned up – Walter Cronkite replaced by Jim Morrison. A quick furtive glance at Dock, and she saw that he hadn’t moved from where he’d been for the past hour – lying back, leaning against the wall, face towards the TV, but with his eyes closed.

She shivered slightly though the room was warm and still. She spotted the spoons with their burned bottoms, tiny pieces of cotton still in the center. She looked back at Dock and her eyes drifted up to see a splatter of blood on the wall and the pole lamp. For a moment, she had the urge to go into the kitchen and find some cleanser or bleach and scrub the evidence from the wall, but was stopped by the sight of a girl she had never seen before leaning languidly against the archway between the living room and kitchen, a needle still dangling from her veins. She had never seen a girl shoot up and this girl’s eyes were closed and she was shifting her weight and her hips were moving slowly back and forth. A soft noise like a purr was coming from deep inside her.

Dock had gotten up, and was standing beside the moaning girl as she leaned into his body.

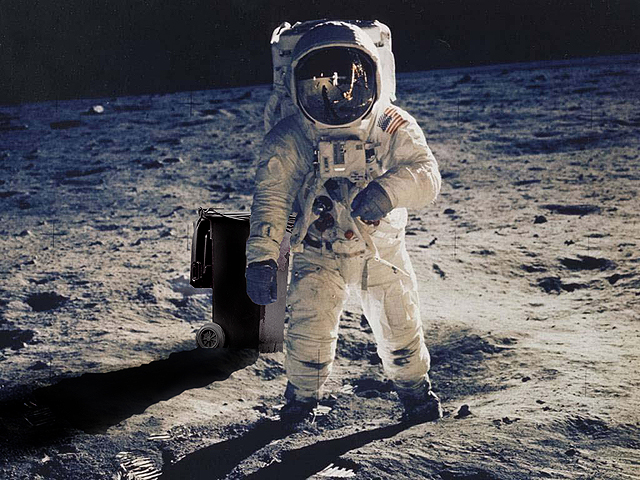

“Damn!” Dock said slowly, as he matter of factly removed the needle from her bruised arm. “Can you fuckin’ believe it? One day we can tell our kids that we watched the men on the fuckin’ moon scagged outta our brains!”

With that, he returned to his spot against the wall, closed his eyes and turned back towards the TV.

Of course there’s more to the story. Of course I never got to Woodstock. It was all in my head anyway. Besides, one week before Woodstock, Dock’s best friend Steve died of an overdose and all of our lives were changed forever. Dock lived to be 50, I understand. Heard he moved to Florida, got married, had children even. I wonder what he told his children about where he was when the men walked on the moon.