There is no place of comfort on the edge.

But then, who needs comfort. She’s been too comfortable her whole life. She sits before the web cam. She turns on the camera and slowly removes her clothes. She’s had three glasses of wine at dinner, but it’s way too early to go to bed.

Click.

She reaches her hand forward, her fingers pressing the mouse to freeze the image, her eyes gazing directly into the shining eye of light at the top of the screen.

Click.

She tilts her head and rotates her shoulder slightly, hoping to make her body look younger.

Click. And click again.

She puts her glasses on and leans forward, squinting at the pictures of herself on the screen. She is surprised by how pink and soft and vulnerable her body looks.

She removes the glasses.

Delete. Delete. Delete.

Later, weeks later, she is once again in front of her computer and she wants to delete something else. She clicks on her recycle bin and is jolted by those images she’d forgotten she had taken.

She clicks on Permanently Delete, shuts down her computer and decides to go outside.

It is snowing. Not that lovely peaceful beautiful snow from the first big snow storm last week, but an a nasty, angry, cold wet snow that burdens the electric wires - she knows that this snow will soon bring darkness, the lack of heat, the cold.

She is not dressed for the cold, but at least she is dressed, she chuckles to herself. Her feet are wet and frozen but she walks on. The cul de sac is long and she makes herself walk so far that it would be equally distant to turn back as it is to move keep moving forward.

She stops. She steps outside herself and sees what others, looking out their windows might see - a ridiculous old woman with no boots, an inadequate coat, and a bare head, trudging through the snow, now, frozen in her tracks.

This is post mid-life, she says to no one, her hands extended towards the sky, her head tilted back, inviting the snow to alight on her nose, her cheek, her eye.

I would rather be walking along the edge than frozen to the ground on a cul de sac.

Let me move to the 30th floor of a city apartment with a view of the river on one side and the expanse of neighborhoods on the other.

My favorite place is on the edge of the city, atop Belmont Plateau. There, the buildings of downtown Philadelphia stretch from bridge to bridge, from river to river. When I worked, I would detour past this spot on my way home everyday and no matter the time or the season, I would always brake - sometimes for several minutes, sometimes only for a few seconds, taking note of the color, the light and the texture of the familiar buildings. There was an energy pulsing through the cement and stone and glass, infusing the skyline with life. And even though the outline and tableaux of the buildings always appeared the same, the mood and the hues and the shadows were infinitely and astonishly different each time I stopped.

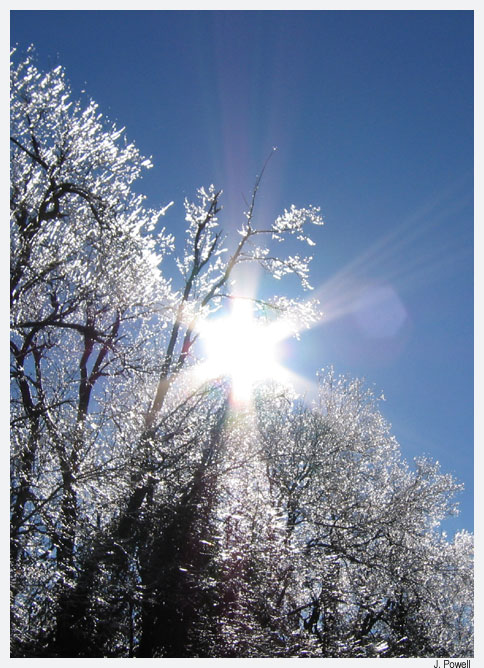

Back in the cul de sac, this tree in winter is what has has stopped her in her tracks. Before her eyes, its stark brown bark and grey branches begin to fade, then disappear completely before turning into pure energy shimmering with light and humming with sound. She stands transfixed until she is embraced by the sympathetic vibrations rising up in her, meshing with the beat of her heart and letting her know without a doubt, that she too is alive.